On June 6th, Peruvians cast their votes in the country’s presidential runoff between two contenders with polarising platforms. Keiko Fujimori, a third-time presidential candidate who remained unpopular with the majority of Peruvians, promised to fight crime with a “hard fist” (mano dura) and to maintain her father’s neoliberal economic policies, which were pioneered in the 1990s and are widely credited with Peru’s recent economic successes.

Contents

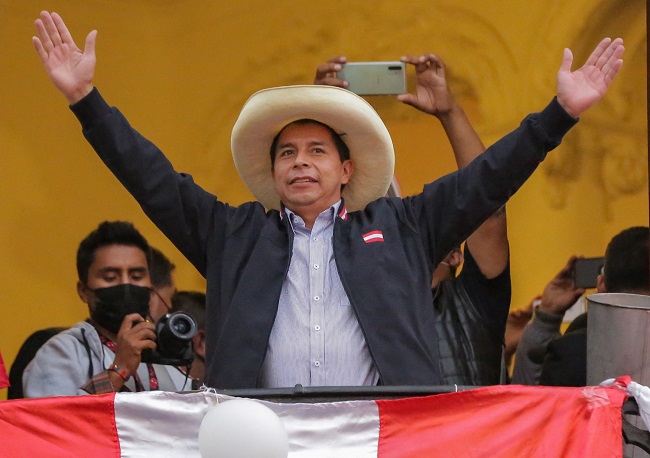

Primary School Teacher and Leader

She faced off against Pedro Castillo, a primary school teacher and leader of a group within Peru’s radical teachers’ organisation (Sindicato nico de Trabajadores de la Educación del Per, SUTEP), who was from the poor northern region of Cajamarca.

Castillo was a candidate for Per Libre, a party led by an outspoken Marxist-Leninist. In order to better meet the demands of the disadvantaged and the impoverished, the party’s policy endorses nationalising mines and calls for a constitutional convention.

One expert consulted for this article compared Peruvians’ options on June 6 to “the cliff and the abyss” due to the stark contrast between the possibly authoritarian right (represented by Fujimori) and an empowered, socialist left (represented by Castillo).

Where did this Torturous Decision Originate From?

What would Castillo’s apparent triumph, which was decided by a margin of just 0.42 percent of the votes cast, imply for Peru?

The clash between Fujimori and Castillo did not just happen; rather, it was years in the making. Peru has had remarkable economic growth and poverty and inequality reductions during the previous three decades.

Despite sporadic crises, the country’s political system has been consistently democratic since 2001, with free and fair elections held on a regular basis; presidents are, importantly, barred from running for reelection within their first term (that is, a former president can only seek reelection once he or she has been out of office for a full five-year term).

Last Words

The relationship between the unicameral Congress of the Republic and the executive branch has become increasingly dysfunctional as a result of the country’s increasingly fragmented party system, which sees multiple established and newly created parties competing in each presidential and legislative election.

Peru, on the other hand, has kept its market economy open, attracted foreign investment, and (until very recently) was seen as a regional success story while its Andean neighbours Bolivia and Ecuador have fallen for radical, left-wing populism under Evo Morales and Rafael Correa, respectively, in the past two decades. Is Peru’s modest but upward trend over now that Castillo seems to have won? Can the still-debatable election results from June 6 bring Peru to a bright and successful future, or is there no hope at all?